What if I'm wrong? Negotiate with yourself to avoid making big mistakes

25/30 - Things like career changes incur great opportunity cost, but you can play the role of both sides of a negotiation not to decide if you should pursue a change, but to avoid disaster

I’m thinking of a career change. Why yes – I am a chronically underemployed creative! Yes, no other real world skills, what gave it away?

Career moves incur Opportunity Costs. Large ones. And if they don’t – fuck you, you lucky bum. Being truly committed to studying something means that you can’t study anything else. There’s always an exclusion. For example, if I study accounting full-time, that might hold off learning traditional animation for, what, 3, 4, maybe even 5 whole years. And what if after five years I only then figure out “Wow, I hate accounting” or “this is not the profitable career change I expected it to be?”. Well that’s five years and thousands of dollars in study fees I’ll never get back.

Then again, you don’t buy a car without test driving. You don’t buy a house without walking into the house, and hopefully getting a conveyancer.

It’s the same principle as prototyping. If you want to start a business, let’s say, making a robotic jacket steamer. You’d first want to be sure your design is possible and practical. Then you want to show it to investors so they can be sure it’s money well spent.

A career change is a lot like building a prototype: you’re both the mad visionary and the investor taking on risk by ponying up the cash.

And even then, after you’ve built a prototype, you can spend a long time trying to get it ready for production and only later on realize you had the wrong approach. Likewise, you can study something for a very long time, sometimes years before bolting up in the middle of the night, in a cold sweat, realizing you’ve made a terrible mistake!

“Damn I should have taken up animation not accounting!”

This is how I go about it: I effectively negotiate with myself. I’m both sides, one wone side I throw out numbers – bids if you will: which might be guesses about how long it will take to accomplish a goal.

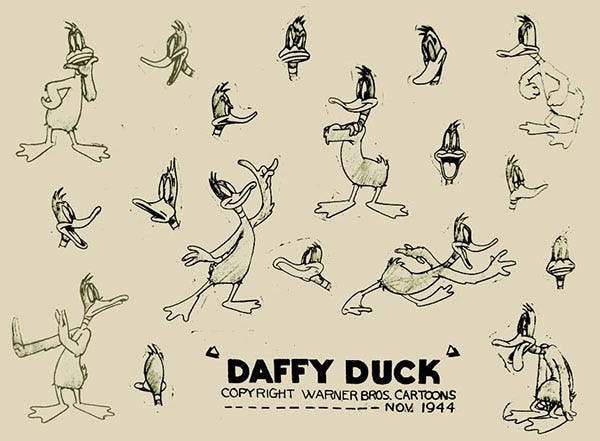

Now imagine that I want to be a traditional animator like Emery Hawkins, or Jim Tyer, or Bill Melendez. These guys injected so much fluidity and emotion into their drawings. At the very least, they all could draw Mighty Mouse or Daffy Duck pretty well.

Just for the sake of argument, let’s say we had a universally agreed upon criteria for what makes a “decent Daffy Duck drawing” (Try saying that five times straight, HOO HOO!). You need not imagine too hard, you can just take a model sheet, say from the 1944 . If you could draw one of those poses freehand, I reckon most people would say “that’s a decent Daffy duck”. Now here’s my first bid: after 5 years of studying traditional animation. I should be able to draught a damn fine Daffy, every single time.

If this is a negotiation, I have to play the other side and counter-bid myself:

So what about after 2 ½ years: if I expect 100% success rate after 5 years, then in half the time I should have a 50% success rate? Now, if you agree with that logic, then the same ratio should apply, so after 1 year of study. If you sat me down to draw 50 Daffies, 10 would be damn fine. And after just one month, one in every 60 Daffies I draw should be damn fine. Agree?

Well no. I don’t agree with that logic at all. But this is interesting, because it is revealing an implicit intuition I have, about how long this learning should take.

To be honest, I expect, if I spend a single afternoon drawing 100 identical drawings. All of on-model Daffy Duck, by hundredth attempt - I would expect to get at least one good one. By the two hundredth attempt I would expect to be able to draw almost every second one well.

Instead of ½ of my draught Daffies being damn fine freehand drawn by 2.5 years… I suspect after merely 200 drawings, over what? Maybe 2 or 3 afternoons, I should manage a 50% success rate. Obviously if I can’t manage that – maybe animation isn’t for me. It’s better to find out after just three afternoon than 5 years, right? You build a prototype first, your test drive the car first.

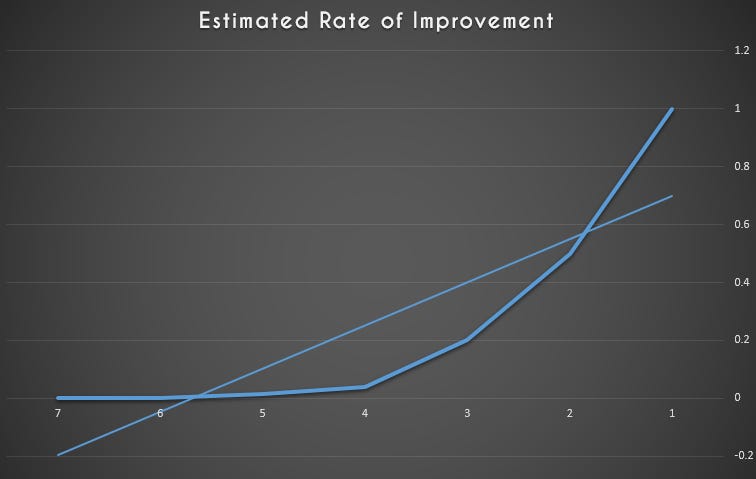

These “bids” are just guesses. Yet remain incredibly useful. if we break the guesses/bids down from years, to months, to single afternoons – we can quantify the expectations. And the implicit plotting of a curve of improvement.

We can even test that curve and see if it holds up.

The exciting part. Because if I’m right that by the third afternoon I can get a 50% success rate, but I can’t get to a 75% success rate after 10 afternoons – that might mean the learning curve is slower than I thought. And I can change my estimates – I’ve pretty much reinvented Bayes Theorem.

However, it’s generally accepted that learning isn’t linear. While you’re mastering the fundamentals, you would expect a slower or shallower learning curve, and after you’ve mastered them a steeper one. Don’t believe me? Then test it!

But if I don’t do this negotiation, just throwing out random numbers based on vibes alone. I don’t even have a model to begin correcting – I can’t even test my expectations.

I might be wrong and never know about it. Now I can quantify it.